INSIGHTS

Risks in the Construction of Hydropower Projects: Unforeseen Ground Conditions under FIDIC

13/11/2023

Get in touch

INSIGHTS

Risks in the Construction of Hydropower Projects: Unforeseen Ground Conditions under FIDIC

November 13, 2023

Get in touch

This article addresses the problem of unforeseen ground conditions in hydropower projects.[1]

Introduction

The construction of hydropower projects is highly dependent on the ground conditions, for both the design and for the construction of dams, tunnels, and power stations. But the unique site-specific characteristics of each hydropower project means that unforeseeable ground conditions are common.

Mother Nature has a habit of playing tricks and serving up the unexpected. No matter how many bore holes an employer sinks pre-tender, it is inevitable that there will be some ground information missing. How can this risk be mitigated and distributed in a cost-effective way?

This article considers the approaches of the FIDIC standard forms, including the FIDIC Emerald Book 2019 (The Contract for Underground Works) in advance of the launch of the FIDIC Emerald Book Guide and Reprint later this month.

The Problem

The key features of hydropower projects are:

- long construction periods;

- high construction risks; and

- high construction [2]

The high construction risks are caused by the unique site-specific characteristics of each hydropower project: in particular, unforeseen ground conditions.

The Impact

If adverse ground conditions are discovered during execution of the works, the contractor may have to adjust:

- its method of working;

- the plant or equipment it is using to carry out the works;

- its programme; and/or

- the design of the

As a result, the project may take longer to reach completion and/or cost more to complete.

The parties must consider these risks, and allocate them appropriately, when tendering a project and negotiating and agreeing the terms of the contract. How should this risk be allocated? What is fair?

Professor Nael Bunni[3] proposes that the following four principles are used for allocating risks in construction contracts:

- Which party can best control the risk and/or its associated consequences?

- Which party can best foresee the risk?

- Which party can best bear that risk?

- Which party ultimately most benefits or suffers when the risk eventuates?

It is easy to argue that the employer should take the risk, because it owns the ground at the site and thus arguably controls the risk, and will ultimately benefit from the finished works. But the employer is not a geologist or specialist engineer with a particular knowledge of constructing hydropower projects.

Whilst the contractor may not have access to the site, it ought to have the expertise to better foresee the risk.

If the contract is silent on this, the law governing the contract will apply. Under the laws of England and Wales, there is little sympathy for a contractor who signs a contract for which completion of the work (in strict accordance with the original design) is impossible. In contrast, under many European jurisdictions’ impossibility may give rise to various equitable remedies whereby the contract can be renegotiated, re-priced, or in extreme cases, rescinded entirely.

The contract conditions need to address this. So, what does FIDIC do about it?

The Solution: FIDIC forms used for hydropower projects

Employers generally choose FIDIC contracts for international hydropower projects. FIDIC contracts are perceived to have a fair and balanced risk allocation. Often the FIDIC forms are modified to reflect the particularities of each hydropower project.

There are two common procurement approaches:

- Engineer, Procure and Construct (‘EPC’) – with single point responsibility. Most risk is placed on the contractor (For example, the FIDIC Silver Book). It has been said that lenders tend to prefer this approach despite it being more

- Split-contract – across several works’ packages. This carries increased interface and co-ordination risk (for example, the FIDIC Red Book for the civil works, the FIDIC Yellow Book for the electro-mechanical works, and a bespoke non-FIDIC interface agreement). There will also be an engineering consultancy services contract (for example, the FIDIC White Book).

FIDIC Red and Yellow Books

The starting point, under the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books (1999), is the Employer’s obligation of full disclosure. The Employer “shall have made available” (mandatory language) “all relevant data in [its] possession on sub-surface and hydrological conditions at the Site“.[4] Environmental aspects are expressly included. This makes sense because the Employer is the only person who can carry out an analysis of the sub-surface conditions at the Site before the contract is tendered. The obligation is a continuing one. It applies before the Base Date, and after the Base Date if any further information comes into the possession of the Employer.

Then, the Contractor must use its expertise to interpret that data.

Further, the Contractor is deemed to have obtained “all necessary information as to the risk, contingencies and other circumstances which may influence the Tender or Works”. This is qualified to the extent by which it was practicable “taking account of cost and time“.

There are additional provisions for adverse ground conditions which fall within the definition of “physical conditions” and are “Unforeseeable“.[5] In such circumstances, the risk is allocated to the Employer. This is right and proper as there is a true cost to a project.

‘Physical conditions’ are:

‘natural physical conditions and man-made and other physical obstructions and pollutants, which the Contractor encounters at the Site when executing the Works, including sub-surface and hydrological conditions but excluding climatic conditions’.

Physical conditions will include geology, hydrology, soil condition, and any contamination of the ground on the Site. Artificial or man-made conditions or obstructions might include antiquities, landfill, asbestos, old sewers, or unexploded ordnances. The term “physical conditions” does not include climatic conditions. The physical conditions must be encountered “by the Contractor at the Site during execution of the Works“. Therefore, the Contractor may not rely on this sub-clause for relief for impediments encountered off the Site.

“Unforeseeable” is defined very broadly as “not reasonably foreseeable by an experienced contractor“. The terms “reasonably” and “experienced” both being open to interpretation (a gift to lawyers). It is worth noting that in the 1999 editions, ‘Unforeseeable’ is defined “…by the date for submission of the Tender“, but in FIDIC 2017 forms (2022 reprints) it is “… by the Base Date“.

Whether or not a physical condition is Unforeseeable is often decided by reference to the site data. Thus, when unfavourable ground conditions are found, such as unexpectedly hard rock, the Contractor will scour the site data for any reference to hard rock. If there is no reference to hard rock the Contractor will argue that its presence was Unforeseeable. But everyone knows that the site data is not definitive. A bore hole survey is only accurate for that precise location.

Therefore, the FIDIC contracts provide for interpretation of the site data by an experienced contractor. Contractors cannot simply take as the definition of foreseeable that which is set out in the site data. This position is reflected in the case law.

Unforeseeable physical conditions were considered in the case of Obrascon Huarte Leon v Her Majesty’s Attorney General for Gibraltar.[6] At that time in Gibraltar, the road to the Spanish border (the Winston Churchill Avenue) traversed the airport runway so that the road had to be closed when the runway was in use. In an attempt to relieve the congestion caused by the frequent closure of this road, the Government of Gibraltar engaged OHL to construct a new dual carriageway road and a twin bore tunnel under the eastern end of the airport runway, known as the Frontier Access Road. There were delays and the Government of Gibraltar terminated the contract. OHL sued the Government of Gibraltar for wrongful termination. Although Gibraltar is famous for its rock and despite the airport site’s historic military use, the OHL argued amongst other things that it had encountered more rock and contaminated material in the ground excavated on site than would have been reasonably foreseeable by an experienced contractor at the time of tender. Mr Justice Akenhead found against OHL and awarded it just 1 day extension of time out of 660 days originally claimed (reduced to 474 days in the amended particulars of claim submitted during the hearing itself).

In the High Court decision in 2014 Mr Justice Akenhead stated:

‘I am wholly satisfied that an experienced contractor at tender stage would not simply limit itself to an analysis of the geotechnical information contained in the pre-contract site investigation report and sampling exercise. In so doing not only do I accept the approach adumbrated by Mr. Hall [the defendant’s geotechnical expert] in evidence but also I adopt what seems to me to be simple common sense by any contractor in this field.’

In the Court of Appeal decision in 2015 Lord Justice Jackson stated:

‘The Judge [Mr Justice Akenhead] accepted the approach of Mr Hall. He held that an experienced contractor would make its own assessment of all available data. In that respect, the Judge was plainly right. Sub-clauses 1.1 and 4.12 of the FIDIC Conditions require the contractor at tender stage to make its own independent assessment of the available information. The contractor must draw upon its own expertise and its experience of previous civil engineering projects. The contractor must make a reasonable assessment of the physical conditions which it may encounter. The contractor cannot simply accept someone else’s interpretation of the data and say that is all that was foreseeable.’

In Van Oord UK Ltd & SICIM Roadbridge Limited v Allseas UK Limited[7] Mr Justice Coulson followed a similar approach stating:

‘Every experienced contractor knows that ground investigations can only be 100% accurate in the precise locations in which they are carried out. It is for an experienced contractor to fill in the gaps and take an informed decision as to what the likely conditions would be overall.’

If the Contractor encounters ‘physical conditions’ which it says are ‘Unforeseeable’ the Contractor must, in short: continue, comply, and notify. It must:

- take all necessary steps and continue with the Works – provided the Works are still possible;

- comply with any instruction which the Engineer may give;

- if it will have an “adverse effect on the progress and/or increase the Cost of the execution of the Works…“, notify the Engineer “as soon as practicable“,

(i) describing the physical conditions,

(ii) explaining why they are Unforeseeable, and

(iii) explaining why they will have an adverse effect on progress and/or Cost; and

- give a Sub-Clause 20.1 notice[8] if it requires an extension of time or

In other words, the Contractor is responsible for completing the Works and the Employer is liable for any increased time and/or Cost (not profit).

The Engineer will then inspect, consider, and determine. It must:

- inspect the conditions;

- consider if any conditions were more favourable than could have been foreseen and, if so, weigh those together with the allegedly adverse conditions; and

- give a Sub-Clause 3.5 determination[9] to agree or disagree with the Contractor’s claim for time and/or Cost and instruct a Variation if appropriate (for which Clause 13 [Variations and Instructions] will apply).

If the Contractor disagrees with the Engineer’s instruction, it may pursue the time/money claim unilaterally.

In the FIDIC Red, Yellow and Silver Books (1999), the Contractor is expressly discharged from further performance if an event or circumstance outside the control of the Parties arises which “makes it impossible or unlawful for either or both Parties to fulfil its or their contractual obligations“.[10]

The FIDIC 2017 forms (2022 reprints) make no fundamental changes.

FIDIC Silver Book

The FIDIC Silver Book (1999) has an entirely different solution. As in the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books (1999), under Sub-Clause 4.10 the Employer shall have made available all relevant data in its possession on sub-surface and hydrological conditions at the Site etc.

However, in the FIDIC Silver Book (1999) the Contractor must verify as well as interpret such data, and most importantly it is expressly stated that the Employer “shall have no responsibility for the accuracy, sufficiency or completeness of the data” (except under Sub-Clause 5.1) – emphasis added.

In the FIDIC Silver Book 2017 (2022 reprint) the obligations are divided across Sub-Clauses 2.5 and 4.10. The relevant data to be provided by the Employer is, arguably, narrower.

The provision dealing with “Unforeseeable physical conditions” in the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books (1999) is deleted. In its place is a clause dealing with “Unforeseeable difficulties” which appears wider in scope. However, under the FIDIC Silver Book (1999) the Contractor carries all the risk for unforeseen difficulties as it is “deemed to have obtained all necessary information as to risks, contingencies and other circumstances which may influence or affect the Works“.[11]

Further:

‘by signing the Contract, the Contractor accepts total responsibility for having foreseen all difficulties and costs of successfully completing the Works. “[12] and “the Contract Price shall not be adjusted to take account of any unforeseen difficulties or costs’.[13]

Under the FIDIC Silver Book 2017 (2022 reprint) there is very little change, most notably that: “the Contract Price shall not be adjusted to take account of any Unforeseeable or unforeseen difficulties or costs“.[14]

Such is the scale of risk being placed on the Contractor, that the Guidance section within the FIDIC Silver Book (1999) itself expressly warns against the use of the FIDIC Silver Book in tunnelling and similar contracts as follows:

‘If the Works include tunnelling or other substantial sub-surface construction, it is usually preferable for the risk of unforeseen ground conditions to be allocated to the Employer. Responsible contractors will be reluctant to take the risks of unknown ground conditions which are difficult or impossible to estimate in advance. The Conditions of Contract for Plant and Design-Build should be used in these circumstances for works designed by (or on behalf of) the Contract’.[15]

This is emphasised in bold in the Notes section at the front of the FIDIC Silver Book 2017 (2022 reprint) as follows:

‘These Conditions of Contract for EPC/Turnkey Projects are not suitable for use in the following circumstances: … If construction will involve substantial work underground … unless special provisions are provided to account for unforeseen conditions ….’

FIDIC Emerald Book

In contracts where there is a high risk of unforeseen ground conditions, the Employer is encouraged to allocate significant resources for geographical surveys of the site and, in particular, any tunnel locations. A geological baseline report increasingly represents good practice and is now commonly required by insurers in UK tunnelling projects. In January 2023 CIRIA published Geotechnical baseline reports: a guide to good practice (C807).[16]

The FIDIC Emerald Book (2019) was the first internationally recognised form of contract specifically drafted for tunnelling. It was drafted jointly by FIDIC and the International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association. It was based on the FIDIC Yellow Book 2017 (which has now been reprinted with amendments). FIDIC has announced it will launch the FIDIC Emerald Book Guide and Reprint in November 2023.

The solution in the FIDIC Emerald Book is the introduction of a Geotechnical Baseline Report (‘GBR’) at Sub-Clause 4.10.2. It is not found in any of the other standard form FIDIC contracts. The GBR is a contract document and, although not expressly stated, it is expected to be prepared by the Employer (usually an expert consultant engaged by the Employer) – although it is possible that the Contractor might be expressly required to prepare the document or collaborate in its production. In the order of priority of contract documents[17], the GBR is placed sixth of twelve. It is defined as the report included in the Contract which:

‘describes the subsurface physical conditions to serve as a basis for the execution of the Excavation and Lining Works, including design and construction methods and the reaction of the grounds to such methods’.

In the Guidance section of the FIDIC Emerald Book, Appendix A: The Geotechnical Baseline Report includes a section on ‘GBR Content Recommendations’ and an Example Table of Contents of a Geotechnical Baseline Report.

In a similar way to the FIDIC Yellow Book, the Employer “shall have made available” (mandatory language) “all relevant data in [its] possession on the topography of the Site, on hydrological, climatic and environmental conditions at the Site and adjacent property, and on the geological and hydrological data of the subsurface of the Site“.[18] The express reference to topography is new. Unlike the FIDIC Yellow Book the obligation is not restricted to the Site but also, in part, to adjacent property. The obligation is a continuing one. The GBR and the Geotechnical Data Report (‘GDR’) are expressly required to be made available. The Contractor must use its expertise to interpret the relevant data.

It is not obvious from the wording in Sub-Clause 2.5 what happens if data provided by the Employer conflicts with the GBR. But Sub-Clause 4.10.2 provides that the Contractor “shall be deemed to have based its Tender and the Contractor’s Proposal for the Excavation and Lining Works on the [information] described in the GBR” and this deeming provision applies even in the event of a discrepancy or ambiguity in any of the other site data provided by the Employer. The definition of Unforeseeable adds weight to the GBR taking precedence.

Errors in the GBR are addressed in Sub-Clause 1.9 and give rise to Variations, time, and money for the Contractor. How this relates to the regime for ground conditions set out in Sub-Clauses 4.12 and 13.8 is unclear.

Further, the Contractor is deemed to have obtained “all necessary information as to the risk, contingencies and other circumstances which may influence or affect the Tender or Works“. This is qualified by the provisions of the GBR and to the extent by which it was practicable “taking account of time and cost and access to the Site and its surroundings“.[19]

In the Notes at the front of the FIDIC Emerald Book, it states that the GBR is “defined as the single contractual source of risk allocation related to [the anticipated] sub-surface physical conditions” and their behaviour (i.e. how the sub-surface physical conditions are likely to act during the construction process). The information which the Employer produces in this report will create an expectation of what the Contractor is likely to encounter. Much will depend on what the Employer puts into the GBR.

As in the FIDIC Yellow Book, there are additional provisions for adverse ground conditions which fall within the definition of “physical conditions” and are “Unforeseeable“.[20]

“Physical conditions” are:

‘natural physical conditions, physical obstructions (natural or man-made), pollutants and reactions of the ground to Excavation, which the Contractor encounters at the Site during execution of the Works, including sub-surface and hydrological conditions but excluding climatic conditions at the Site and the effects of those climatic conditions’.

“Unforeseeable” remains broadly defined as “not reasonably foreseeable by an experienced contractor…by the Base Date“. However, it is then narrowed quite considerably (in relation to ground conditions) by the wording “Notwithstanding the foregoing, all subsurface physical conditions described in the GBR are deemed to be foreseeable, and all subsurface physical conditions outside the scope of the conditions defined in the GBR are deemed to be Unforeseeable”.[21]

In other words, it redefines the boundary of Unforeseeable by what is and is not included in the GBR – sub-surface physical conditions described in the GBR are foreseeable, and sub-surface physical conditions not described in the GBR are unforeseeable. The “reasonably foreseeable by an experienced contractor” test plays no part in respect of the sub-surface and hydrological conditions, which makes it easier for the Employer to compare contractor bids.

Because of this black and white divide (sub-surface physical conditions described in the GBR being foreseeable, and those not described in the GBR being Unforeseeable), the Employer might adopt a cautious approach in the preparation of the GBR by incorporating every potential ground related risk.

This possibility is recognised in the Guidance section of the FIDIC Emerald Book. Appendix A: The Geotechnical Baseline Report states, “the Employer should avoid establishing an overly conservative GBR” and “the Employer is advised to provide realistic statements … to give the tenderers confidence“. In other words, the Employer should avoid requiring the Contractor to price for improbable ground conditions, in an endeavour to place as much risk as possible on the Contractor, as this may result in higher initial bids. The Contractor will be entitled to money both where the physical conditions fall within the GBR in the form of rates and prices set out in the Bill of Quantities (presumably with an allowance for profit) under Sub- Clause 13.8, and where the physical conditions do not fall within the GBR as Cost (no profit) under Sub- Clause 4.12. So, an “overly conservative” GBR might work in the Contractor’s favour.

Whether or not the sub-surface physical conditions fall within or are outside the GBR determines the Contractor’s claims procedure.

- Sub-Clause 4.12 [Unforeseeable Physical Conditions] covers Claims for unforeseeable physical conditions which fall outside the limits of the

- Sub-Clause 13.8 [Measurement of Excavation and Lining Works and Adjustment of Time for Completion and Contract Price] covers Claims for sub-surface physical conditions which are within the

Under Sub-Clause 4.12 (for unforeseeable physical conditions which fall outside of the GBR), if the Contractor encounters “physical difficulties” which it says are “Unforeseeable” the Contractor must continue, comply, and notify. It must:

- continue execution of the Works;

- comply with any instructions which the Engineer may give;

if it will have an “adverse effect on the progress and/or increase the Cost of the execution of the Works…“, notify the Engineer “as soon as practicable and in good time“, (i) describing the physical conditions, (ii) explaining why they are Unforeseeable, and (iii) explaining why they will have an adverse effect on progress and/or Cost; and

- give a Notice under Sub-Clause 20.2 if it requires an EOT or

The Engineer will then inspect, consider, consider again, and determine. It must:

- inspect and investigate the conditions;

- consider “whether and (if so) to what extent the physical conditions were Unforeseeable“;

- consider if any conditions were more favourable than could have been foreseen (but not more favourable conditions covered by Sub-Clause 13.8.3) and, if so, weigh those together with the allegedly adverse conditions; and

- give a Sub-Clause 3.7 determination to agree or disagree with the Contractor’s claim for time and/or Cost (no profit), and any instruct a Variation if appropriate (for which Clause 13 [Variations and Instructions] will

Under Sub-Clause 13.8 (for sub-surface physical conditions within the GBR), the excavation and lining works will be remeasured. The Contract Price and the Time for Completion will be adjusted following such measurement (without the need for a formal Notice). The Contractor undertakes the measurement (by default on a monthly basis) and the Engineer will agree or determine the measurement under Sub-Clause 3.7.

The time allowed in the Completion Schedule – a contractual document stating the Time for Completion for the Works/Sections/Milestones “based on and consistent with the production rates provided by the Contractor in the Baseline Schedule” – and/or the Programme is reassessed. It is reassessed by applying the agreed/determined measurement to the production rates set out in the Schedule of Baselines – a contractual document setting out details of anticipated activities or items of work and their corresponding quantities “based on the subsurface physical conditions described in the GBR, and their corresponding production rates as provided by the Contractor“.

The Contract Price is adjusted by revaluing the agreed/determined measurement at the appropriate rate or price for each item in the Bill of Quantities, and by applying the time-related items in the Bill of Quantities.

The Practical Effect

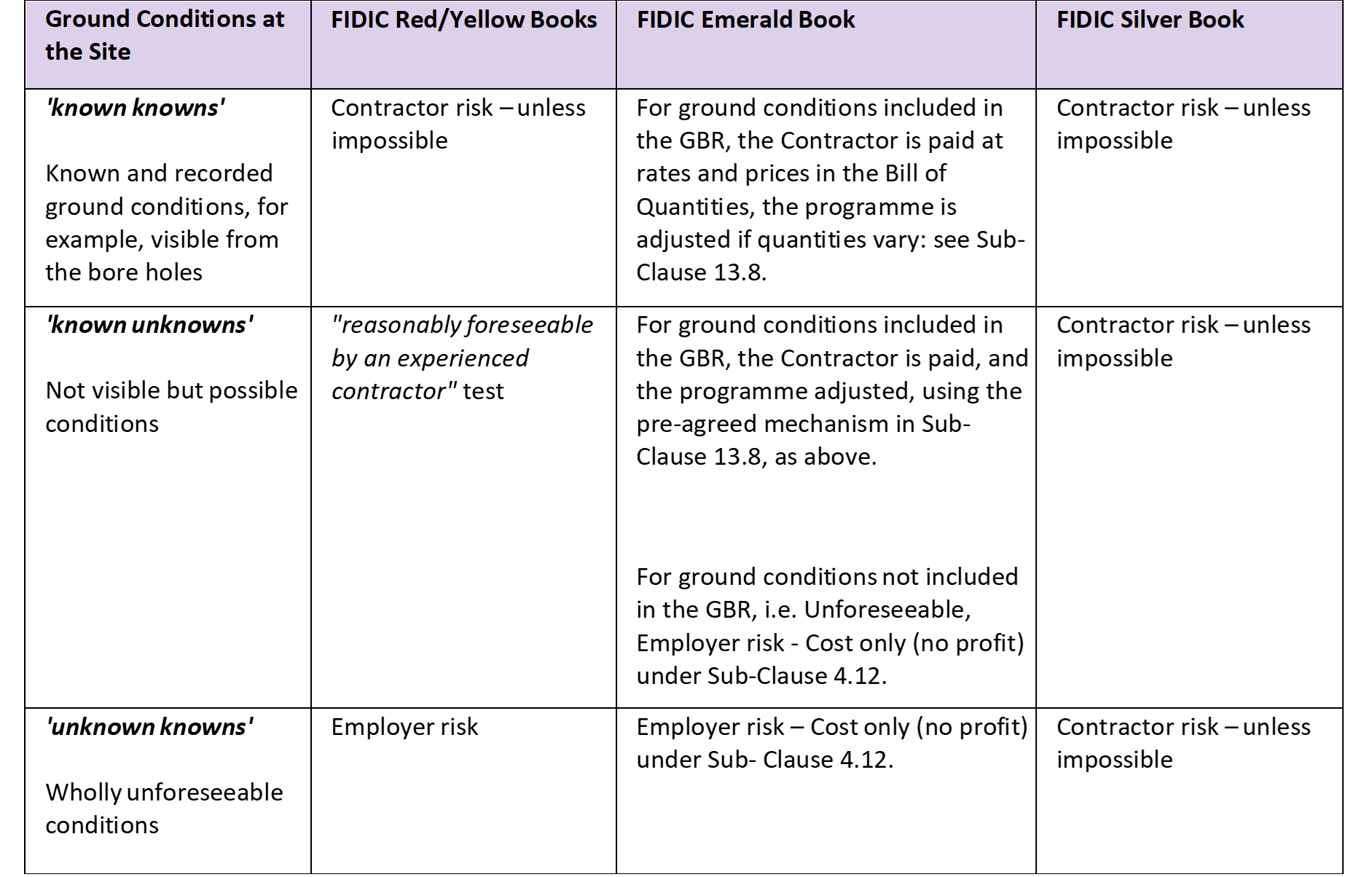

The practical effect is best illustrated by example in the table below:

In other words, the Employer carries more risk for adverse ground conditions in the FIDIC Emerald Book (2019) than in any other FIDIC form.

Conclusion

The concept of geotechnical baseline reports is sound, and there is much support for them within the industry. The FIDIC Emerald Book (2019) has made a good start but requires refinement.

Where the contract includes tunnelling work and the other work would have been let on a Design-Build basis anyway, then the FIDIC Emerald Book is an option. If the civil works would otherwise have been a FIDIC Red Book, then the GBR provisions could be added to the FIDIC Red Book instead.

The GBR has removed much of the debate about what is Unforeseeable in relation to underground works.

But when the Contractor’s incurred costs exceed the rates and prices in the Bill of Quantities, we can expect many arguments about what is in the GBR and what is not and thus Unforeseeable.

The key take-away is to get the risk allocation right for your project from the outset. Allocating a risk to a party who cannot sustain it is futile and will lead to failure.

We can help guide you through the options for what is best for you and your project.

Please get in touch at victoria.tyson@howardkennedy.com with your thoughts or to discuss any concerns.

[1] This article is a summary of the issues discussed by Victoria Tyson at the HYDRO 2023 Conference in Edinburgh, on 13 October 2023.

[2] Alex Blomfield, ‘Key issues in the procurement of international hydropower construction contract’, International Construction Contract Law, 2nd edition (2018).

[3] Nael Bunni, ‘The Four Criteria of Risk Allocation in Construction Contracts’, International Construction Law Review, Vol. 20, Part 1 (2009), p. 9 [PDF page 6].

[4] Sub-Clause 4.10.

[5] Sub-Clause 4.12.

[6] [2015] EWCA Civ 712.

[7] [2015] EWHC 3074 (TCC)

[8] Sub-Clause 20.2 in the 2022 reprints.

[9] Sub-Clause 3.7 in the 2022 reprints.

[10] Sub-Clause 19.7.

[11] Sub-Clause 4.12 (a).

[12] Sub-Clause 4.12 (b).

[13] Sub-Clause 4.12 (c).

[14] Sub-Clause 4.12 (c).

[15] FIDIC 1999, Guidance, Sub-Clause 4.12.

[16] Authored by John Davis, Randell Essex, Imran Farooq and Antony Drake.

[17] Sub-Clause 1.5.

[18] Sub-Clause 2.5.

[19] Sub-Clause 4.10.1.

[20] Sub-Clause 4.12.

[21] Sub-Clause 1.1.101.

Please click the button below to read the full article.